This classic introduction to the modern fairy tale sets a story in the distant past, usually in a land far far away, and changes the tone of everything that follows. It’s possibly one of the most powerful narrative devices in the English language.

After we hear those words, we expect that everything that follows will be whimsical and probably fictional. If a story starts with ‘once upon a time,’ you shouldn’t be surprised if a fairy, witch, or some other magical creature appears. The words ‘once upon a time’ instruct the reader to suspend their disbelief.

It’s as old as the fourteenth century, Chaucer used it and there was a variation in the tale of Sir Ferumbras. The history of its use parallels the history of the fairy tale itself. In The Wonder of a Kingdome (1636), Thomas Dekker uses it to convey a mode of telling stories orally: “Cannot you begin a tale to her, with once upon a time there was a loving couple…”

The written fairy tale was properly invented in the salons of the next century and the fairy tale, as we know it, was invented the century after that by our beloved Victorians, who took all of the naughty bits out and started saving and creating these stories for children. The Victorians did this to so many stories they had to make up a word for it in 1836:

bowlderize: to expurgate (a book or writing), by omitting or modifying words or passages considered indelicate or offensive; to castrate.

The changes, modifications, and invention of the fairy tale follows shifts in culture socially and economically, like nationalism. Nationalism is also a very Victorian word, which was coined in 1798 to describe a phenomenon that was already underway.

nationalism: Advocacy of or support for the interests of one’s own nation, esp. to the exclusion or detriment of the interests of other nations. Also: advocacy of or support for national independence or self-determination.

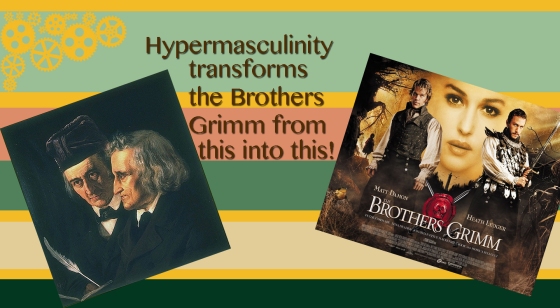

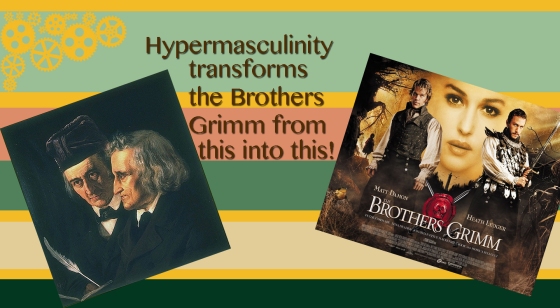

The Brothers Grimm were motivated by nationalism. They wanted to protect the stories that were uniquely and historically German from the increasing (even militant) influence of French culture. Before the rise of nationalism, people were generally loyal to their regions. It took the French and American Revolutions to make people think of themselves as devotedly part of a larger national whole, or like they had any role in shaping what belonging to that whole actually meant. Hence, the interest of the Brothers Grimm in creating a record of a distinctly German identity.

Before the Brothers Grimm told their stories, academics were gathering in salons to share fairy stories. These stories were meant for other scholars and were often made up by the scholars themselves. The women, who hosted the salons told stories of aristocratic females, suffering some sort of oppression, who was saved by magic, or came to a terrible end for failing to abide by the social sanctions of her time. Thus, these stories mirrored the experiences of the writers themselves.

Then the industrial revolution happened, which created a new middle class and an idealized concept of what it meant to be a child. Before the industrial revolution, social mobility was a fairy tale of its own (Cinderella), and whole families generally worked together as an economic unit. Children were expected to contribute to the household through labour. The industrial revolution centralized the capitalist system moving labour outside of the home and creating new socio-economic systems.

The Victorian interest in evolution and psychology contributed to the belief that childhood should be a time of personal development, during which one gains the skills they need to successfully contribute to the economic system in adulthood. Consequently, children didn’t need to hear about the real world. Fairy tales were and still are a great insulating tool, especially once the naughty bits are taken out.

What naughty bits do I mean?

In Rapunzel, the witch figured out that Rapunzel had been secretly letting the prince into her tower because Rapunzel was pregnant.

In Little Red Ridinghood, Red and her grandmother obviously die. They were eaten by a wolf! What do you expect?

The original Snow White is a girl of about ten years old, which is way too young. Also, the stepmother asks for the girl’s heart because she wants to eat it.

In Speeping Beauty, the prince does more than just kiss the sleeping princess, and before she awakes, she gives birth to twins.

Today, scholars debate the usefulness of these stories, particularly because we still like to tell them to children. The main argument is that it fills children’s heads with warped ideals of masculinity and femininity. In some cases, stories are modernized, or given a new twist, to make them appeal to modern readers. I spoke about hypermasculinity in my last post.

These stories definitely present warped ideas, but if we have to share the story of a warped idea, there may as well be fairies and dragons, or what have you. Maybe a story doesn’t have to be useful.

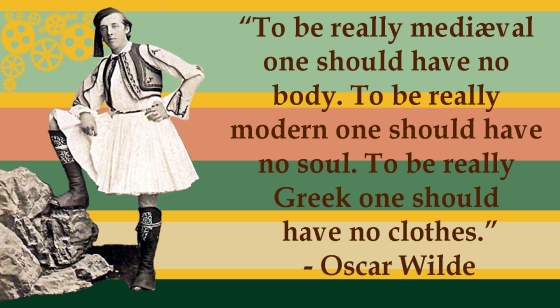

As Oscar Wilde said, once upon a time:

There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.

Support the project through my GoFundMe page, or visit my shop.