If you want to learn about a different culture, learn its language. Even if the language is the same, the time and context of otherwise familiar words can change their meaning. At least, this has been my experience when studying French and German, as well as in my investigation of the late Victorian era. That being said, some people will tell you that if you want to learn about a different culture, you have to eat its food.

Victorians loved their cake. The word cake has Scandinavian roots and, in Middle English, described a flat bread roll. The first thing I find, when searching the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) for 19th-century words containing “cake,” is ash-cake, which first appeared in English in 1809 and refers to a cake that is cooked in the ashes of a fire. This recipe was popular in English colonies, where resources were scarce. Looking over that recipe, I think it needs more butter, and then, I want a scone!

Through colonizing the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Creek People, English-speakers learned to make corn cake, a cake often associated with the American South, which actually belonged to its indigenous people.

“Baby-cake” doesn’t mean what you think it means, but is a seventeenth-century word that was still popular in the nineteenth century and used to describe cakes with a prize baked inside. The prize might be a bean, though I can’t imagine being pleased to find a bean in my cake, but coins were popular hidden treasures as well. I remember my mom baked me a birthday cake like this once when I was a child.

Sponge cake recipes date back to the seventeenth century, but they weren’t called such until one was named after Queen Victoria, who ate them every day! Saturate that cake in alcohol, or cordial, for a chance to use another Victorian word: “tipsy-cake.” If it’s saturated in booze, you’d think it would be properly drunk, but “tipsy” is a more delicate word by a mile.

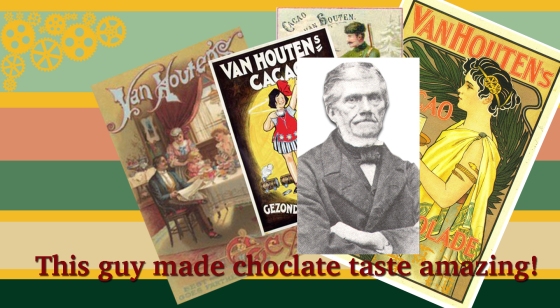

In 1801, Coenraad Johannes van Houten was born in Amsterdam. He would grow up to be a chemist, who would make chocolate cheaper, saltier, sweeter, and easier to use, introducing Dutch Chocolate to the world and allowing the creation of modern conceptions of chocolate, like chocolate-, or “cocoa-cake,” an 1883 word.

The OED places the coining of the term “pat-a-cake” back to 1883, but, if you view the term as a variation of “Patty Cake,” it goes back to Thomas D’Urfey’s The Campaigners (1698).

Patty cake, patty cake, baker’s man, Bake me a cake as fast as you can; Pat it and prick it, and mark it with a B, Put it in the oven for baby and me.

In nineteenth-century American slang, however, “patty cake” referred to the pastry, while “pat-a-cake” described the game played with clapping hands. “Patty cake” might have been used to describe one of America’s greatest inventions, until the term “cupcake” was invented. The first American cookbook writer, Amelia Simmons invented the cupcake with her publication of American Cookery (1796), but Eliza Leslie (also American) coined the term in 1828.

Now, if you will excuse me, I might just go and bake a cake with one of, my friend, Lili’s amazing recipes!

Support the project through my GoFundMe page, or visit my shop.