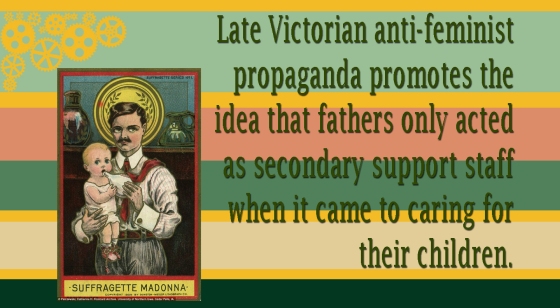

Any reference to the notion of Victorian fatherhood typically brings to mind an image of a distant and sever man. Dr. Julie Marie Strange challenges that image in her new book: Fatherhood and the British Working Class, 1865-1914″ (2015), and the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) supports her findings.

Strange found that Victorian fathers were as hands-on as today’s dads, talked about the same way, and had affectionate relationships with their children. Likewise, the OED indicates that more synonyms for “dad” were created during the nineteenth century than at any other point in history.

The long list of Victorian pet names for dads may simply reflect the fact that more words were created during the Victorian Era, or it could be a reflection of a broader trend in the history of fatherhood. Words like “paw” (1826), “governor” (1827), “pop” (1828) and “bap” (1842) sound overwhelmingly affectionate, leading me to conclude that Victorians must have been talking, reflecting, and writing about fatherhood more than ever before.

But this “more than before” aspect is part of the trend, as Strange’s research found that Victorian dads were being praised as “new men” and better parents than their fathers had been, something every generation of fathers has been told since.

Lost for words to describe how you feel about this? A few more synonyms for dad might help.

da (1851) a pet name for dad in the nursery, or around the house

baba (1863) a way to call one’s father, when speaking babytalk

pops (1893) also used to address a jazz musician

poppa (1897) a pet name for your dad, lover, or husband

Whatever your kids call you now, I hope all the dads out there have a happy Father’s Day this weekend.

Support the project through my GoFundMe page, or visit my shop.